Now that we have concluded our reading of Ibn al-Jazzār’s Risāla fī’l-khawāss, the Epistle on Special Properties, let us see how it touches on some fundamental questions on the value of experience and experiment vis-à-vis theoretical knowledge.

The Risāla is a small work that alternates between a few theoretical paragraphs and an abundance of “examples” to justify its scientific thesis. The thesis, grosso modo, is that one should not rely on theory alone and much less on hearsay alone when considering the extraordinary natural properties and effects of some substances. Following every iteration of this line of argument, Ibn al-Jazzār provides us with a wealth of examples to make his point, citing an impressive roster of traditional authorities. Here is a sample,

According to al-Tabarī, when the tongue of a hoopoe is hung above someone who is forgetful, he will recover his memories. // They say that when you take a fang from the upper left jaw of a crocodile, and hang it above someone afflicted by fever, his fever will go away.

Naturally, during our reading we had many occasions for good cheer with the sometimes outrageous and often bewildering examples, commenting on how we should make sure to acquire this or that particularly helpful substance, like body parts of tortoises or lions. But beyond the banter, two points are worth reflecting on: 1) the vanity of rational understanding in the face of the marvellous, and 2) the unquestionable value of experience when reported from trustworthy authorities.

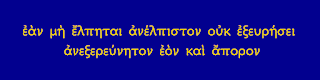

Ibn al-Jazzār goes almost as far as ridiculing the attempt at rationalising the wondrous properties of nature, making a perennially valid epistemological point: how can you claim that something is impossible or absurd, and not simply a reflection of shortcomings in your perception and understanding? This attitude is precisely the acknowledgement of and openness to “anomalies” that, in Kuhn’s language, may give way to needed new paradigms.

The second point follows: you have to stubbornly trust your own experience of the phenomena or, if not your very own (and here comes the twist), the experience of fully trustworthy authorities. That is, the chain of authorities is not hearsay and not mere bibliography, it is as if we ourselves had seen the fever abate under the crocodile's fang, and memories return under the hoopoe’s tongue. I may not have been there and made these experiences with crazy substances, but I trust Aristotle, and Galen, and Apollonius etc.

As ever, we find here how directly our very modern and cutting-edge questions are in conversation with medieval authors, and how from subjects like magic, alchemy and all that “crass baseless superstition” we are questioned, and indeed assayed and improved in our theory and our practice. Ergo, if you have some Arabic, don’t hesitate and join our weekly reading group, restarting in September. [J. Acevedo]